The Baltic states have been a place where European history is decided.

Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania are historically intimate with the threat of invasion from both east and west. Part of the “Bloodlands” defined by historian Timothy Snyder – which also encompass Belarus, Poland and Ukraine – the countries endured the worst of both Nazi and Soviet atrocities in the first half of the 20th century. After World War 2, the Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania were swallowed up by the Soviet Union until 1989, when Lithuania was the first of the Soviet Republics to declare its independence.

After decades of stability, the sovereignty of European countries is under attack again, and the Baltics have wasted no time in hardening their media infrastructure against outside threats, from kinetic, cyber, and disinformation attacks.

An increasingly unstable border

The frequency of kinetic – ie, physical – violations of European sovereignty is rising. In October a barrage of balloons was flown into Lithuania from Belarus, resulting in Lithuania closing its borders with Belarus. In November a second barrage was sent over the border, shutting down Vilnius airport.

Also in October, Estonian border guards reported seeing armed men, wearing no insignia, in a village along the Estonia/Russia border – appearances that recall the “little green men” – soldiers in unmarked uniforms – seen near Ukraine and Crimea before Russia’s initial invasion in 2014.

Latvia is currently assessing how to dismantle railway tracks leading in and out Russia. Rail networks have always been an essential feature of Russian war logistics. Earlier this year, the country closed some border crossings with Russia and Belarus to pedestrians and cyclists.

But threats in the digital world have been a regular part of Baltic life for some time. In 2007 a DDoS attack, almost certainly of Russian origin, brought down large parts of Estonian public infrastructure, including broadcasters. The attack was a wake-up to the region – and to the world. A year later, NATO’s Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence (CCDCOE) was set up in the Estonian capital Tallinn.

The fully digital nature of broadcast and media infrastructure and its integration with public life, makes it a juicy target for cyberattack.

Latvian TV choosing cloud for disaster recovery

During the Soviet period, Russian became the language of government in the country. Today, the official language is Latvian but around 34% of the population still claim Russian as a first language, the highest proportion in any Baltic country. Russian speakers live mostly in the east, bordering Belarus and Russia, and in the big cities

The country has already attempted to protect the information space by closing up some Russian-language content outlets feared to be platforms for Russian disinformation. The country’s National Electronic Mass Media Council (NEPLP) revoked the license of independent Russian-language channel TV Rain, but a Latvian court has overturned the decision.

But as incursions ramp up, and the balance of power on Europe’s eastern border becomes more uncertain, ensuring the physical integrity of broadcast has become more center stage.

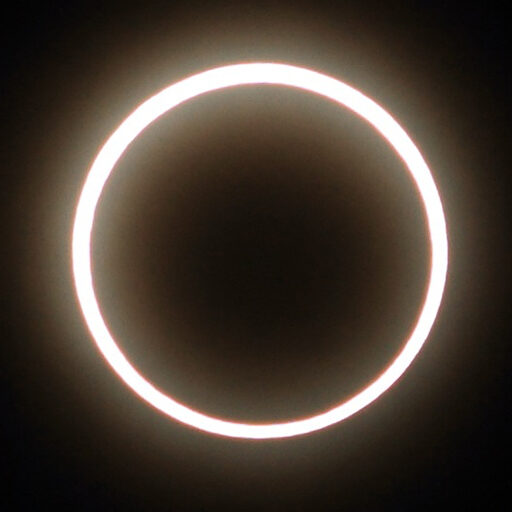

The Riga Radio and TV Tower (see image above) is the third tallest broadcast tower in Europe (after the Ostankino tower in Russia and the Kyiv TV Tower in Ukraine). Latvian Public Media, rebranded this year after the merger of Latvian Television (LTV), Latvian Radio (LR), and online portal LSM, is rethinking how it can keep its channels on air in the event of a major incident.

Disaster recovery for broadcasters has often meant redundant physical infrastructure operating in parallel. If a master control center goes down, or an essential cable is accidentally dug up, or a malicious attack disables a site, the signal can be rapidly switched to an alternative, physical infrastructure.

This method allows instantaneous, potentially seamless, recovery, but there are downsides. One is expense. Redundant hardware installations can be a strain on budget, especially for a function that will only be used in exceptional circumstances. Another is that you are still committed to a certain amount of physical infrastructure which can limit a broadcasters mobility in an emergency situation.

The alternative is the cloud. Cloud back-up doesn’t respond as instantaneously as a physical, “on the ground” solution will. But the time it takes to spin up is outweighed in most cases by the benefits of paying only for what you use and almost endless flexibility in location.

Latvian Public Media has turned to cloud for its new disaster recovery solution, not only for the benefits listed above but because of a government mandate that the national broadcaster’s recovery center must be a minimum of 1000 kilometers from the Russian border. The new solution uses Veset as the playout solution for a cloud-back up located in date centers in another part of the EU.

“The broadcaster’s main issue was that they were running backup for the whole country to one main data center in Latvia,” explains Veset CTO Martins Magone, “but there was nothing, in the case of an actual hot war happening, that couldn’t be just bombed – and then we have no television. It needs to be somewhere far away, where they could still probably reach, but wouldn’t risk it.”

The Latvian Public Media is essentially a “cold” back-up, where content has been prepared and stored but none of the cloud instances are actually running. Using cloud for broadcast applications has been approached with caution by Baltic countries, but disaster recovery is an easy entry point for starting to employ cloud tech. And the cost benefits aren’t insignificant – with this kind of cloud back-up, the broadcaster pays virtually nothing until the back-up stream needs to be activated.

Veset’s all-in-one SaaS playout solution, Veset Nimbus, keeps disaster playout streamlined and simple. Nimbus features browser-based functionalities like scheduling, encoding, playout, and graphics so there’s no requirement for additional technology, or on premises systems, to get a channel back out to the public.

The platform is a self-managed service, which means that the user is fully responsible for all sources, graphics, emergency messaging, or playlists which will start broadcasting once the cloud playout is fully activated. Veset also offers some onboarding, which could include custom development for each broadcaster. An API can help integration into pre-existing workflows or playout infrastructure

Latvian Public Media told ¡AU!: “Veset Nimbus cloud playout is used as a back-up solution because of the geopolitical situation. They have really prepared, tested and used the system. All the risks are taken seriously”

But should there also be a backup for the backup? Reliance on a single cloud provider, especially when some US-based tech providers appear to be bending more readily to political pressures, may not be the safest bet. A good disaster plan needs to be simple, but not overreliant on a single vendor that you can’t pivot away from if you need to.

“We try to keep our offering at Veset generic,” says Magone. “Whichever cloud you want to use can be used. You could use multiple clouds in parallel, but not every customer is willing to pay for that kind of super-duper extra safety.

“At the same time, there are hybrid models that work for some customers, where they might have a playout in the cloud, and a playout on prem. They may have some existing product from a vendor that makes it easy for a backup solution. But sometimes it’s better to not use only one manufacturer’s products, in case something happens with that vendor,”

Country by country defense

There have been conversations between the three Baltic states about how their broadcasters could rely on each other for back-up and support in an emergency, and cloud is a part of those discussions. This could include sharing any spare capacity with one another. But no roadmaps or concrete plans have been announced, and despite the cooperation between the countries, any Baltics-wide broadcast security solution is likely to be several years away.

Veset has had interest from Finland as well, with everyone in the region thinking more about how to secure infrastructure and make sure content is available to the public, but disaster response plans will continue to be drawn up country by country and company by company.

“There is increasing risk awareness,” says Veset COO Lelde Ardava, “Currently, we are talking to the national regulator that we might contract for the smaller, regional broadcasters. It’s a long-term project.

“Latvia is a small country, and the Baltics have a huge border with Russia and Belarus. Some of the broadcasters’ systems are old school and outdated. Cloud would help assist them in having a plan B if something happens. They could turn it on and in a few minutes be able to send information nationally in a short time. And regional television stations might be affected first in any attack, since they are close to the border.”

European Commissioner for Defence Andrius Kubilius addressed the November Defending Baltics conference in Vilnius in November.

“One of the most important questions for the European Union and for NATO is how to defend the Baltics and how to learn from Ukraine” He added that European intelligence services have said Russia could be willing to “test Article 5 in the next two or four years”.

As early as January 2024, Vladimir Putin was claiming that Latvia and other Baltic states were “throwing [ethnic] Russian people” out, a situation which he said, “directly affects [Russia’s] security” – a line of argument used endlessly as a pretext for annexations, whether in Ukraine 2014 and 2022, or Czechoslovakia 1938.