The mood on the ground at last week’s IBC Show in Amsterdam was that of a broadcast industry winding down. A sector getting ready for a nap. A long, long nap.

Remember how at the end of Alien, the eponymous courgette-headed monster lies huddled amongst the ducts, sliming away, yawning? It’s as if the Alien has come to the end of its natural lifecycle and just wants to be left alone to die. Or maybe it’s popped a six-fingered handful of dramamine hoping to sleep through the whole flight – “Wake me when Antarctica Control calls”. In any case, he has called it a day.

So that is what the broadcast industry looks like right now – a slimy, once formidable, Alien going to sleep.

But how can an industry pelted by emergencies – uncertain revenue, tech change, fickle audiences – fighting heroically for its future, be going to sleep? What about cloud? And AI? And all those new efficiencies?

Market complacency

The one thing that came up in virtually every conversation I had with exhibitors IBC was how vendors and their broadcast customers are working to adjust and adapt to circumstances created by others. The tendency is always toward the reactive, rather than the creative. Broadcasters sound like they are commanding a battallion on the retreat, waiting for enough supplies so they can hold until spring, but with no hope of victory. This is true for some – but not all – of the streamers too, who are scrambling to keep subscribers and crank out attractive content without breaking the bank. Change is looming, but too often the solution seems to be to hunker down and keep optimizing what you’re already doing.

The Nobel Prize winning economist Paul Krugman wrote about the collapse of markets on his Substack in a piece titled “Why Aren’t Markets Freaking Out?: Of Trump, Keynes and Wile E. Coyote“:

“My read of economic and financial history is that market pricing almost never takes into account the possibility of huge, disruptive events, even when the strong possibility of such events should be obvious. The usual pattern, instead, is one of market complacency until the last possible moment. That is, markets act as if everything is normal until it’s blindingly obvious that it isn’t.”

The inimitable Nathan Tankus summarizes this by saying that the market is not, as stylized economic models would have us believe, a mechanism that pools the knowledge and informed judgment of millions of investors. It is, instead, a ‘conventional wisdom processor.’ That is, it reflects views that seem safe to hold because many other people hold them — and the crowd only abandons those views when they become blatantly unsustainable.”

You could feel the underlying unease at IBC. Attendees could hear those “huge, disruptive events” outside, getting closer and closer. But the problem with abandoning what isn’t working is that, by definition, you have to move to something new – and often it’s not just new, but unknown. That takes courage, and more than that, it takes responsibility and commitment. “Better the devil you know, than the devil you don’t”, goes the saying. It’s not true though. It’s just something we say to avoid the responsibility of making decisions.

So many of the new technologies on display at IBC make it easier, faster, cheaper to recommit to the status quo and avoid having to commit to a new direction. They make an implicit promise that you won’t have to change, that you can avoid having to make some difficult decisions. That was a reasonable offer ten years ago, when social media and digital platforms were still threats on the horizon, rather than the enthroned conquerors they are today.

Big media has plateaued

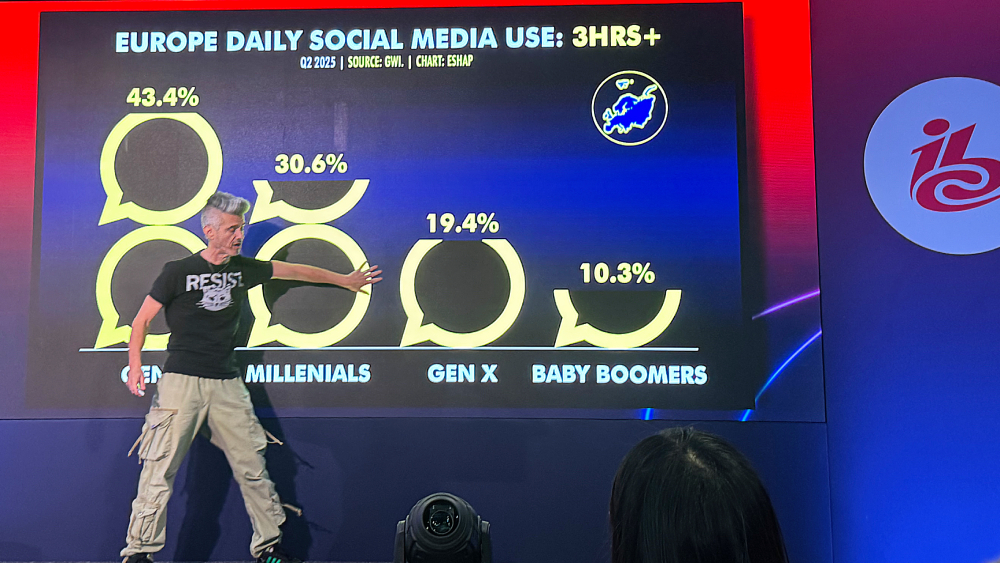

There were two talks in the IBC Conference sessions that provided good perspective on this industry paralysis. In one, Evan Shapiro, the self-styled “Media Cartographer”, known for his engaging data visualizations, hit his audience over the head – repeatedly – with the idea that broadcasters are doomed unless they go – that means to move toward something – to where their audiences are spending their media time, which is on social platforms.

Pointing to the numbers, Shapiro said: “Big media has plateaued, while technology has continued to expand.”

He reminded the room that those Millennials who the industry often still thinks of as a young audience are forty with kids, and it turns out they didn’t turn to linear broadcast on the living room TV as they settled down, as analysts had predicted. They are watching the living room TV, but they’re watching YouTube on it alongside games, steamers, and occasionally a live sports event.

In another session, TikTok’s Head of Global Head of Sports Partnerships, Rollo Goldstaub, presented a similar take. Media audiences (specifically TikTok audiences) are now in control of their content experience, he asserted. And they expect that to be norm now. The notion that you have to work to a big media platform’s content schedule seems just dumb.

Goldstaub said that sports brands and broadcasters need to meet audiences where they are, rather than trying to entice them to come back to their platforms. His stats showed a TikTok that was already a huge hub for sports fans, and he flogged some of the TikTok’s new initiatives and tools for making it easy for sports brands to engage directly with a TikTok audience. The driving principle was that social media platforms aren’t competition with broadcasters, they an essential fuel for success.

I had disagreements with both speakers – I don’t believe, for example, that social media users, on any platform, are “in control”, but I do firmly believe a multi-platform social video space that puts users first is possible, if we all put some work in. And Shapiro’s presentation had too much emphasis on a “the audience is always right” populist vision of content commissioning, which has its place, but I think is still more reaction, rather than creation.

Surrender to the collapse

It’s very possible that the best way to save broadcast is to let it collapse.

And if we let it collapse, I bet we’ll be surprised. Rather than everyone walking away from a smoking ruin of an industry, broadcast professionals may see that they’re surrounded by amazing infrastructure, tech, talent and money that they have been misusing for years.

There are huge changes on the horizon, driven by economics, climate, geopolitical ruptures, etc, and some of what we take for granted is going to be up in the air eventually anyway. Why not get a head start and lay out your assets on the table and start from scratch.

Content recommendation engines don’t do much to filter out noise anymore, they now offer users different types of noise to choose from. What will distinguish content in the future is quality. There are players betting that an AI-boosted strategy focusing on frequency and volume will win out, but “the most noise wins” is only going to work for a short time.

Traditional media companies make media. Not always efficiently (see Frankie Boyle’s joke about the BBC being a thousand Shakespeares typing frantically to eventually produce the work of a monkey). But, as if it needs to be said again, younger people who didn’t go to private schools, need to be in decision-making posts at big tech companies.

Feel free to keep the cranky old bastards in accounting but to get a resurrected broadcast sector on top again, you need to get in floods of young maniacs and give them the tools for commissioning, producing and distributing content – at scale. Say, “Here’s a very powerful studio. Here are some tech geniuses to advise you. Start playing, please.” They will make a mess of some of it, but in a year you’ll have the best multi-platform content slate going. And the content company that produces high quality material to distinguish itself from The Noise will attract audiences and advertisers.

The very real economic challenges of making big changes are outside the scope of this little think piece. But I realize broadcast decision-makers have clawed their way up various ladders for long years. They are not going to give up salaries and pensions – and revenge on everyone who bullied them in school – that easily. They are locked in until retirement, and they are happy to go down with a sinking ship if it means they can pay their kid’s final year at uni. But economic challenges are coming, no matter what we do.

Welcome home, Alien

Given the changes ahead, it’s surely better to choose to jump than be forced to jump. Don’t wait for Ripley, with her TikToks and her Instagrams, to be forced to wake you up with a blast of steam.

Resist too the natural urge to try to eliminate TikTok Ripley for good – “This shuttle ain’t big enough for the two of us (or three of us if you count Jones)” is a losing strategy..

Instead, approach TikTok Ripley with open (six-fingered) jazz hands and admit there’s been a communication gap. Apologize and let her know that you were scared of all the flamethrowers and flashing lights and the loss of control that you’d been enjoying for decades, and that now you going to join Ripley (and Jones) in the adventure ahead.

In fact, with your vast experience of travelling around the galaxy, you can safely pilot the shuttle home and watch over them both while they sleep.